The first human traces in the area of Bambarone La Masseria

In our first article ‘What do we know about the history of Bambarone La Masseria‘ we looked at the actual history of the Masseria.

Perhaps you are also interested in how long and why this part of Puglia has been inhabited since time immemorial?

The first traces of human presence date back to the Pleistocene ice age. Southern Italy was covered by glaciers at high altitudes during the Ice Age, but the climate remained comparatively mild but very dry even during the coldest periods. A well-preserved female skeleton was unearthed in nearby Ostuni and dated to the incredible period between 26.461-26.115 BC (on display at the Museo Civico of Ostuni) https://www.ostunimuseo.it/museo-civico/.

But apparently the Paleolithic hunter-gatherers moved on to other areas or died out; in any case, there is no genetic evidence of them after the Cold Maximum. One reason for this could be the extinction of their usual prey due to the dry steppes that developed.

Photo: Elvira Visciola by https://www.preistoriainitalia.it

Stone Age settlers – the immigrants came from the east across the sea

Our area around Bambarone La Masseria, the so-called Murgia, has been permanently inhabited and cultivated since at least the Neolithic period (10,000-2200 BC). Genetic studies show that settlers, as well as plants and animals, arrived by sea from the eastern Mediterranean. Colonisation first took place along the coasts of Puglia and then spread inland along the rivers. One of the advantages of this area, as already mentioned, was the numerous natural cavities in the ground. The water that collected in these karst caves could be used even during periods of extremely low rainfall. The people used them as dwellings, especially on the edges of the riverbeds, and the natural resources were abundant with the once rich forests and wild shrubs, including olives, and the nearby coast.

When the large water-filled hollows were uncovered, they attracted many pigeons, a much sought-after game meat, as well as other game. In fact, the name of our town, Fasano, comes from these numerous pigeons: Fasi means pigeon in Greek, which became Fasciano and then Fasano.

From the 6th millennium BC, the cultivation of land – wheat, rye and beans – and the breeding of domestic animals – mainly dogs, goats, sheep, pigs and cattle – became established in southern Italy. These cultures gave rise to complex religious rites and the first settlements in small villages of perhaps 25 people, which were not yet permanently inhabited. Neolithic Italy, unlike other Stone Age cultures, still lacks all signs of a hierarchical society, such as rich burial sites or examples of monumental architecture.

First settlements in the Bronze Age – ports for Mycenaean sailors

At the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, during the Bronze Age, the first truly permanent settlements appeared, especially along the Apulian coast; places such as Bari, Monopoli, Polignano, Egnazia and Torre Santa Sabina were already regularly used as ports. Between the 17th and 12th centuries BC, merchants from the powerful and wealthy city of Mycenae (on the Peloponnese in the Aegean Sea) established an extensive trading network in search of resources as far as the Italian coasts, including Sardinia and Sicily. The Apulian coastal towns also served as important stopping points for even more distant goods, as evidenced by the amber found in Egnazia from as far away as the Baltic Sea.

At the same time, in the hinterland, people settled in small communities and lived from agriculture and animal husbandry, although finds show that animal husbandry was clearly predominant. Supplemented by hunting, fishing and wild fruits such as olives, figs and acorns, people now found enough food in one place to give up nomadism. Under the influence of Mycenaean immigrants, the art of brewing beer and processing milk arrived in Puglia as early as the 2nd millennium BC, along with the production of pottery and the style of tombs. Sheep’s wool was worked on looms, as evidenced by weaving weights, and the secretion of the local purple snail was used to dye fabrics.

The red earth of the Murgia was ideal for making pottery, and the technique of throwing clay was imported from the Aegean. Large earthen pots buried in the ground were used to store food and water.

From the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, influences from northern Italy, the other side of the Adriatic and the Aegean also brought metallurgical processing to Apulia.

The numerous remains of Bronze Age burial sites testify to the hierarchical structures that existed, while trade goods and production surpluses favoured the emergence of an elite. Megalithic burial and ritual sites have been preserved in Puglia, a fine example being the dolmen of Montalbano in the Fasano area.

https://www.viaggiareinpuglia.it/de/dettaglio-attrattore/dolmen-montalbano

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Di Geppi Simone, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia commons

New immigrants from the Balkans and the establishment of Greek colonies

With the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age (between the 11th and 10th centuries BC), a new population appeared: the Iapigi. The origin of these immigrants has not been conclusively clarified; the ancient historian and geographer Herodotus suggests that they came from Crete, while another theory points to Illyria in the western Balkans. What is certain, however, is that there was another immigration from outside and that they were absorbed into the Messapian population.

Are there any nearby attractions?

From the 8th century BC, the Greeks also established permanent colonies in Italy as part of their expansion. The port city of Egnazia, inhabited since the Bronze Age, was the northernmost centre of ancient Messapia (roughly modern Salento, the south of Puglia). Egnazia, whose archaeological remains are very close to Bambarone La Masseria, was strategically located on a high rocky promontory, surrounded by two natural creeks, ideal for landing ships. Since Egnazia is practically on our doorstep and its late antique structures are well preserved, we would like to take a closer look at Egnazia and recommend a visit!

https://www.comune.fasano.br.it/pagina55_egnazia-il-parco-archeologico.html

The archaeological site of Egnazia

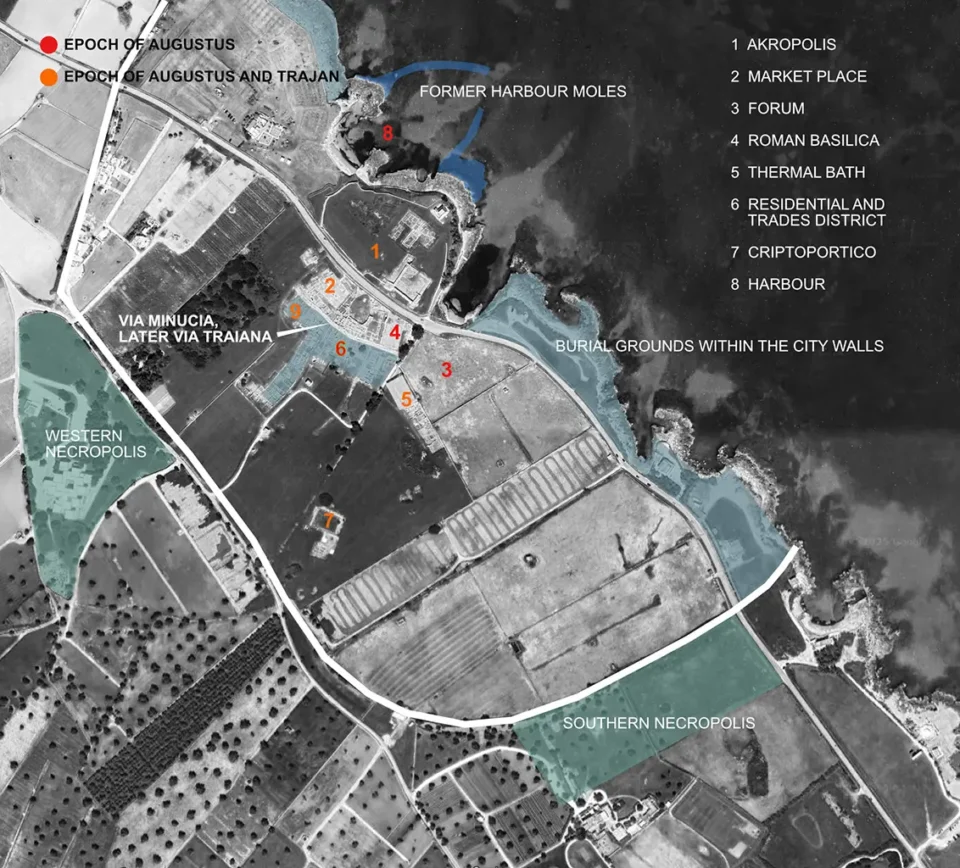

After the first huts on the rocky promontory (the so-called acropolis) and the burial mounds along the coast, some of which can still be seen today, the increasing Greek influence in the Messapian period brought with it the construction of the first public and religious buildings. It is a somewhat bizarre pleasure to see the burial chambers dug into the rocky coastline at the ArcheoLido beach.

Burial chambers on the coast at the ArcheoLido beach near Egnazia

The remains of a temple dating from the 6th century BC have been preserved on the acropolis, and the settlement began to specialise in residential, craft, cult and burial areas. Whereas before the dead were sometimes buried in the huts themselves, now people began to build their own necropolises outside the city walls, some with elaborate chamber tombs. The burial chambers that have survived are particularly interesting: the walls and ceilings show the remains of magnificent paintings, and monumental stone double doors have survived to the present day. These tombs were used by the same family for many generations; the bones of the long-dead were kept in a special niche in the wall (ossuary), while the body was laid on a wooden bed or on a bench carved into the rock (southern and western necropolis).

Photo: MentNFG, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, a wide, 8-metre-high ring of walls was built to protect the acropolis and the city to the south, an imposing section of which can still be admired at its original height. Right next to it, you can see the whole thing from the water, swimming from a small, beautifully secluded beach cove. The wall enclosed an urban area of no less than 140 hectares, a public marketplace surrounded by porticoes, the first theatre complex and other temples built entirely in the Greek architectural tradition.

Photo: Fabrizio Garrisi, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

From Ancient Greece to the Roman Empire

Foto: Fabrizio Garrisi, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

After the Roman victory in southern Italy against Greek colonial rule in 265 BC, Egnazia, like the whole of Messapia, became part of the Roman Empire for the first time.

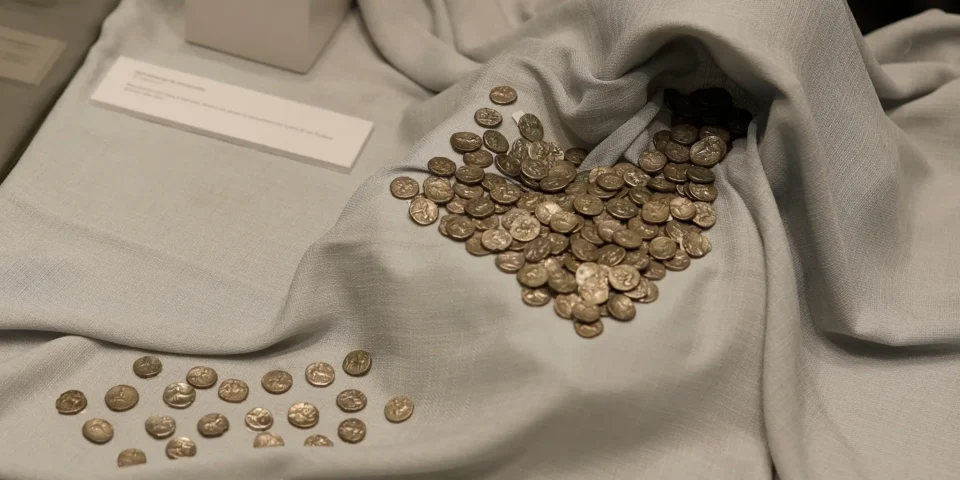

During the Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.), the struggle of the Carthaginians under Hannibal against the Roman Empire, battles were also fought in southern Italy. Most of the inhabitants of southern Italy had joined Carthage to defend themselves against Roman domination. During this time, a very wealthy person must have buried a large number of valuable coins in great distress – as many as 179 silver coins dating from the period between 275 and 212 BC were unearthed in 1933 during construction work at Fasano railway station. The treasure was apparently never recovered, and with the defeat of Taranto in 212 BC, Rome’s victory was secured. It is therefore likely that the area of Bambarone La Masseria was already part of the larger Egnazia settlement in ancient times, as the railway station is only a few minutes’ walk away. The coins are on display at the Egnazia Museum, which is well worth a visit.

https://www.comune.fasano.br.it/pagina55_egnazia-il-parco-archeologico.html

Egnazia’s importance under Emperor Augustus

In addition to its significance as an important port, Egnazia also benefited from its strategic position on a road that ran from Brindisi along the Adriatic to Rome, a shorter alternative to the Via Appia, which passed through Taranto. It was precisely this strategic importance that led to significant urban transformations during the Roman Civil War, which can still be seen today. After Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC, war broke out between Octavian and Marcus Antonius, who fought for sole control of the Roman Empire. This ended in 27 BC with the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Roman Imperial era; Octavian was victorious and henceforth called himself Emperor Augustus. As patron of Egnazia, his son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa promoted the extensive expansion of the port, the construction of a grid of roads, the building of a Roman forum flanked by a courthouse (the Basilica Civile) and thermal baths, now according to the Roman canon.

Photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=945490

The Via Traiana and Mediterranean trade

Between 109 and 114 A.D., under the Roman Emperor Trajan, the ancient route by the sea from Brindisi to Rome via Benevento was extended and further fortified. From then on it was called the Via Trajana and is known as one of the most important Roman roads. The remains of these paved roads can still be seen today, with their deep ruts testifying to their intensive use over a long period of time.

Via Trajana and the market place of Egnazia

Egnazia’s trade relations were extensive until late antiquity: in addition to wine from the Ionian and Tyrrhenian coasts, Apulian olive oil was exported on a large scale and found its way to Palestine and Alexandria in locally made amphorae. Ceramics and oil lamps were imported from the Orient and Africa. From the 1st century AD, trade also increased with other Roman provinces such as Spain, Gaul and Dalmatia, and wine was increasingly imported from the eastern Mediterranean. From the Trajan period onwards, trade relations with North Africa also intensified and continued until late antiquity. Accordingly, the port was of great importance until the middle of the 6th century AD, after which it was only used by the remaining settlers until it was finally abandoned in the 13th century.

Drawing: https://commons.wikimedia.org

Photo: parolediburro, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the next article, we will look at the reasons for the collapse of the once so important ancient city of Egnazia and how the region continued with the arrival of a new religion: “How did early Christianity, the Middle Ages and foreign cultures shape the land around Bambarone La Masseria?”

Are you curious?

Would you like to immerse yourself in antiquity in one of Italy’s most enchanting regions?

Use Bambarone La Masseria as a base for your journey of discovery – you can book here