The Ottomans at the gates of Europe

The last article, How did early Christianity, the Middle Ages and foreign cultures shaped the land around Bambarone La Masseria, showed how much this period has left its mark on Puglia

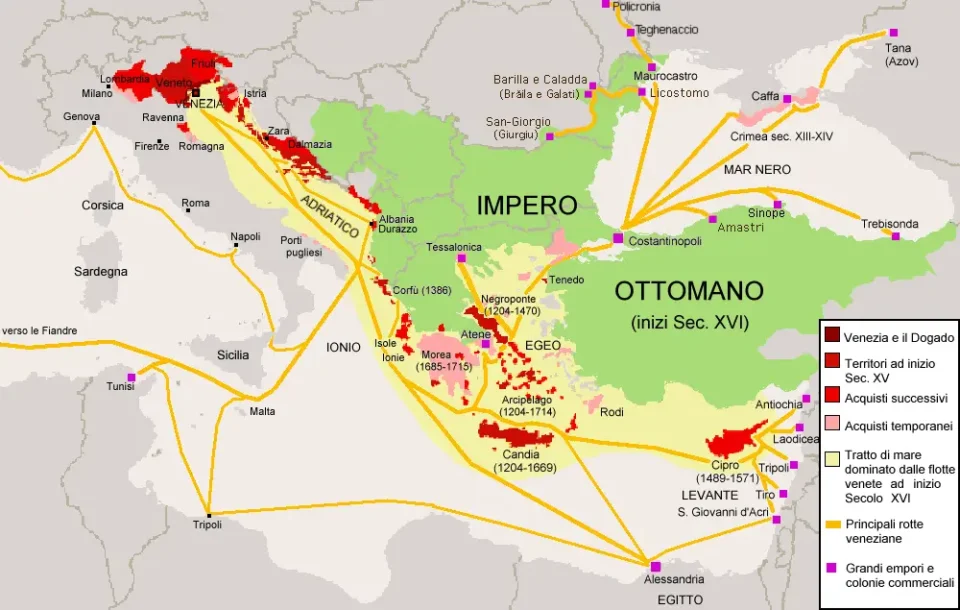

After the crisis of the 14th century, the military expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans represented a new and lasting threat to the coastal areas of Puglia. The conquest of Constantinople by Sultan Mehmed II in 1453 sealed the end of the Byzantine Empire and a new superpower competed with the Italian Republics of Venice and Genoa, the Papal States and the Order of Malta for economic and political supremacy in the Mediterranean.

At the end of the 14th century, Serbian Macedonia, including the coast of present-day Albania, and Bulgaria fell to the Ottoman Empire, which for the first time became a direct neighbour of the European empires. In 1480 Otranto was attacked and destroyed by the Ottomans. Although the Spanish restored their rule the following year, the coasts of Apulia, like all the coasts of the western Mediterranean, remained extremely vulnerable to the constant raids of Ottoman and Berber pirates in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The numerous remains of fortifications and watchtowers along the Apulian coast from this period, which can still be seen today, bear witness to the enormous threat. Often built within sight of each other, they could send signals when enemy ships were approaching. The campaigns of Emperor Charles V in Tunis around 1535 brought some relief, but the Ottomans maintained their supremacy in North Africa.

Photo: kayac, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: PicsAngelo, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The foundation of the typical Puglian masseria in the 16th century

The foundations of the region’s typical architecture were laid in 1566, when the royal landed estates were transferred to the hands of the municipal authorities, who then leased the land in relatively small plots. Famines during the Little Ice Age on the one hand and a growing population on the other led to a certain pressure for change in the 16th century. Agricultural production had to be significantly increased compared to pastoralism, and the possibility of self-sufficiency became more necessary than ever.

The concentration of the rural population in the fortified cities began to diminish, and more and more farmers settled permanently outside the city walls, creating self-sufficient farms dedicated to animal husbandry, olive and vine growing, cereals, legumes, fruit and citrus trees. The oldest masserie still standing today date from this period. Scattered throughout the countryside, they are characterised by their centuries-old olive trees.

Photo: Lupiae, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Giugi30, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Why were some Masserie in Apulia built like castles?

The constant threat from the coast, which was still present in the 16th century, is also reflected in the way the Masserie were built at that time. The farms were fortified like castles, with high walls enclosing the entire complex, including the cattle yards, storage rooms and oil mills. A single staircase, or even a drawbridge, provided well-defended access to the living quarters on the upper floor, which were often protected by loopholes or openings for pouring hot oil directly above. You will look in vain for large window openings. As well as providing protection from the scorching sun, wall openings were reduced as much as possible and secured with strong grilles. Some masserie near the coast also had towers to keep a constant lookout. Some masserie were also built as extensions or annexes to former fortified towers.

Beautiful masserie in the Bambarone La Masseria area:

https://www.pettolecchiacollection.com/en/la-fortezza.html

https://www.masseriamaccarone.it/

https://www.masseriagarrappa.com/

https://www.abbaziasanlorenzo.it/en/

https://www.terredifasano.it/lasciati-ispirare/il-tempietto-di-seppannibale/

https://masseriatorrecoccaro.com/de/homepage

https://www.brundarte.it/chiesa-di-san-pietro-in-ottava-fasano-br/

https://www.masseriatorrelonga.it/

Photo: Henriette Schneider

Photo: Henriette Schneider

The Knights of Malta as feudal lords and coastguards

However, the largest estates were still owned by religious orders, in particular the Knights of Malta, who ruled Fasano as feudal lords from the 14th century. Founded in the 11th century as the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, after the First Crusade it changed from a hospitaller order, caring for the sick and the needy, to a spiritual order of knights with the main objective of leading the fight against the ‘infidels’. From 1358 they took over the former Benedictine abbey of Santo Stefano (completely preserved, near Monopoli) as their headquarters and for centuries were responsible for protecting the coastline from pirates and slave raiders. They were also responsible for the disembarkation of pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land. Until they were confiscated by Napoleon at the beginning of the 19th century, their estates in Apulia stretched from Venosa to Trani, from the Gargano to Lecce and Otranto. A successful knight was rewarded with a commandery (an administrative district of the order), which provided a generous income. There are many testimonies to the wealth and prestige of the Knights of Malta in this area, and from the 17th century Fasano was even the headquarters of the Order. The current town hall was once the imposing residence of the Knights of Malta, before it took on its present form in 1897.

Photo: Dominchio, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: unknown

Fairytale trulli – a city as a tax-saving model

Another truly unique feature of the Puglian landscape has to do with the feudal landlords and the tax laws of the foreign rulers. Alberobello, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the only town in the world to have originated as a trulli town. These trulli – pure dry stone structures with conical roofs – can still be found in their simplest form in many fields and olive groves. They served as sheds and stables and were quickly built with the stones that had to be cleared from the fields.

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The area of Alberobello, then called Selva, was given to the Count of Conversano in the 15th century as a reward for his fight against the Ottomans. The land was forested and uninhabited, so the counts sent peasants to cultivate it. In 1550, the reigning count gave them permission to build stone buildings, but without mortar or lime. The reason for this was to avoid taxes: at that time, any new urban settlement required the approval of the Royal House of Naples, and this was subject to the payment of taxes. In order to avoid this, the Counts of Conversano required the inhabitants to be able to quickly demolish their buildings in the event of a royal inspection. It was not until 1797 that Alberobello was declared a town by royal decree and freed from these restrictions. The peculiarity of Alberobello is that here the trulli were forcibly built as dwellings for the people, close together.

The trulli were built directly on the rocky ground, without foundations, and this construction method and shape is truly unique in Europe. Roughly hewn blocks of stone from the area are laid in two layers, with a filling of smaller stones and earth, to form a thick dry stone wall, without any mortar. The conical roof was constructed with conical stones on the inside and larger flat stones on the outside to make it rainproof. Outside, a narrow spiral staircase led to the roof. Until they were legalised, these trulli were very spartan, with at most a small window opening and a fireplace; nothing more was worth the effort.

The walls were whitewashed inside and out, and symbols were painted on the roof tiles to ward off evil. Rainwater was collected in a cistern dug into the ground. As the family grew, another trullo was simply added, and this is how the trullo complexes can still be found even outside Alberobello. The origin of this construction method is controversial: it could have come from northern Mesopotamia (modern Turkey) or it could have been a purely local invention that developed spontaneously. In any case, they add a magical touch to the Apulian landscape and testify both to the ingenuity of their builders and to the archaic frugality of the people, who lived through centuries of abject poverty.

https://www.inpugliatuttolanno.it/in-puglia/i-trulli-di-valle-ditria-tra-miti-e-realta/

Photo: Acquario51, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the final article of our blog series, we trace Puglia’s rocky road to industrialisation and modernity: How did people experience modernity in the region of Bambarone La Masseria?

Would you like to see the masserie and trulli of Puglia with your own eyes?

No photo or description can replace the magic of the Puglian countryside with its unique and ancient testimonies of history. Discover the places that remind you of the Wizard of Oz with their trulli buildings.

Immerse yourself in the world of knights, monks and peasants under the southern sun and the glittering Adriatic Sea – book your stay at Bambarone La Masseria here