The beginning of a new era – Egnazia becomes a bishop´s see

In the previous article, How did the people of Bambarone La Masseria live in ancient times?, we described how far back the settlement of this attractive area of Italy goes and what specific importance the region of Bambarone La Masseria had in ancient times.

And what happened after a new monotheistic faith arrived in the region?

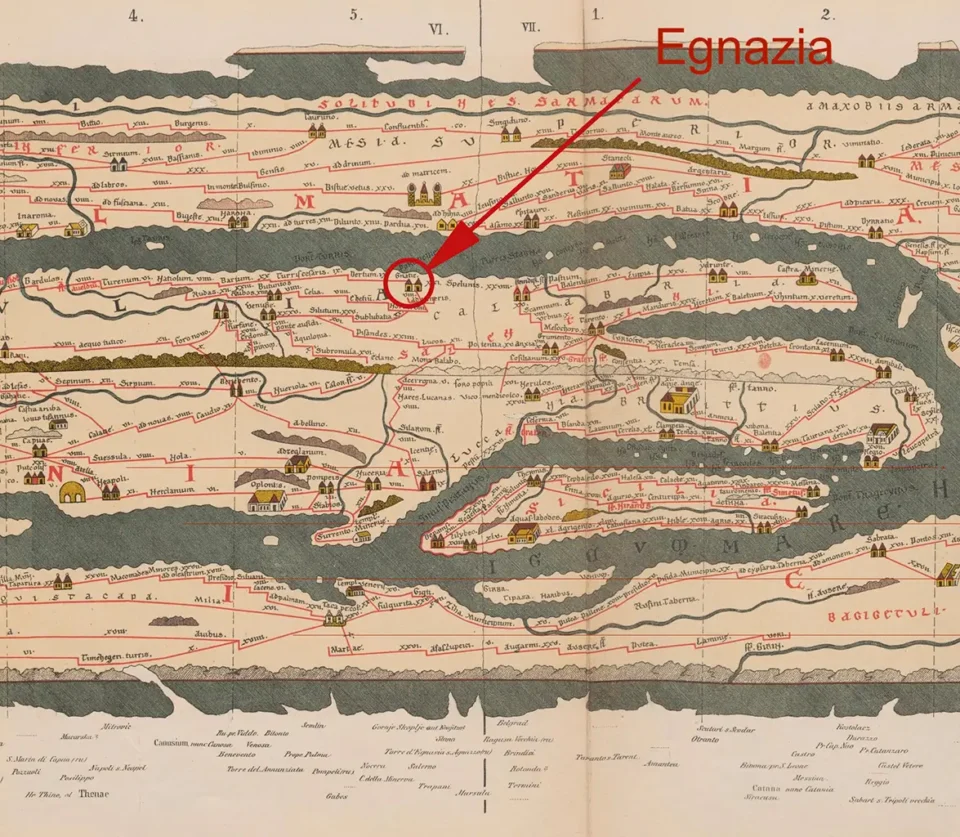

The destruction caused by an earthquake in 365 A.D., on the one hand, and the far-reaching reforms introduced by Emperor Constantine (Roman Emperor from 306 to 337 A.D.), on the other, led to a profound change in Egnazia. As emperor, Constantine was the first to actively promote the spread of Christianity and its institutions, with the result that the traditional polytheistic cults quickly lost their importance.

It seems that Egnazia was chosen as one of the first and most important dioceses of the Christian Church – the first episcopal basilica with a baptistery was built as early as the end of the 4th century. The ancient courthouse on the Forum (civil basilica) was converted into a Christian basilica. At least until the beginning of the 7th century, Egnazia’s economy and trade continued to flourish, with lively exchanges with North Africa and Asia Minor.

Photo: Fabrizio Garrisi, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Fabrizio Garrisi, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Marble burnt to lime – the end of Greco-Roman antiquity

The new religion led to extensive urban redevelopment: in addition to the rebuilding and reconstruction of sacred buildings, trade and crafts were promoted and corresponding buildings were constructed.

The numerous building sites led to an increased demand for lime and bricks, and the thermal baths were transformed into a kiln from the first half of the 5th century. Antique sculptures and marble facings were ruthlessly crushed and burned to make lime, while ceramic and shell fragments were turned into cocciopesto – a high-quality, waterproof wall and floor covering. This flooring can still be found in buildings today, mostly on roof terraces; for centuries it was a traditional and reliable method of waterproofing flatroofs. Even today, local craftsmen have kept this knowledge, but they charge a lot for it.

Even the central temple on the Acropolis was used as a source of building materials from the mid-4th century BC. Hearths and numerous amphorae indicate that it was used as a living and storage space. During the Justinian period (527-565), an early Byzantine fort was built on the acropolis to control the harbour, which was still important, and the Via Traiana. The fort remained in use until the 11th century, and possibly until the 12th century.

Egnazia was also one of the stops for early Christian pilgrims who used the Via Traiana to embark on their journey to Jerusalem from Brindisi or Otranto. The account of a pilgrim from Bordeaux who stopped in Egnazia on his way back from Jerusalem dates back to 334 AD.

Photo: Fabrizio Garrisi, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Ulrich Harsch Bibliotheca Augustana, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Why were the people of Egnatia forced to abandon their city?

It seems that around the middle of the 7th century, floods caused the inhabitants to abandon the southern part of the city and retreat to the Acropolis and the walled areas. The increasingly destructive floods were caused by the deforestation of the surrounding forests.

The Gotic Wars (535-553) also marked the politically unstable period between the 6th and 7th centuries. The Gotics were a former East Germanic people who settled in south-eastern Europe during the Migration Period. In 545, the campaign of the Ostrogoth king Totila against the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian led to the destruction of the city of Egnazia. In the following century, the diet seems to have changed dramatically: only local produce could be eaten, except by a small elite on the Acropolis, there was a great shortage, and even cats were eaten in considerable numbers. With the collapse of the Roman Empire, overseas trade relations and the flourishing economy ended, and the production of olive oil for export ceased.

Graphic: Cplakidas, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Graphic: The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

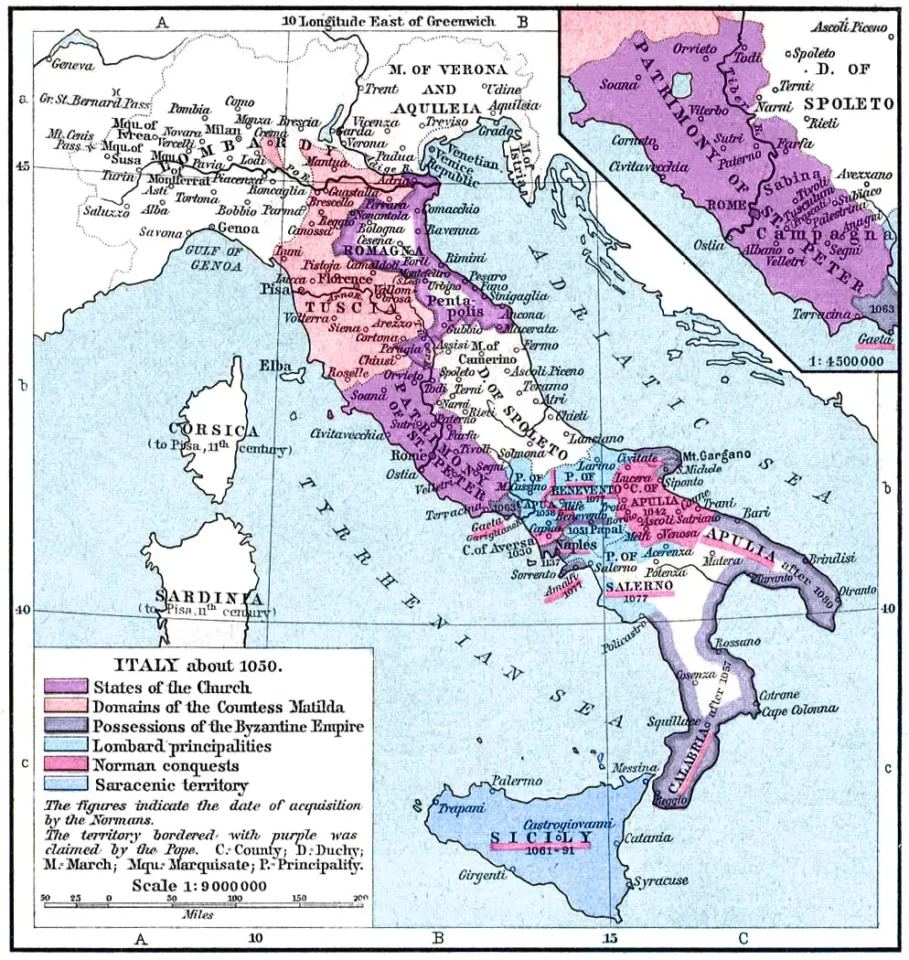

Throughout the early Middle Ages, the region was fiercely contested. Italy was divided between the Germanic kingdom of the Longobards and the Byzantine Empire. Bari was an Arab emirate from 883, and Taranto and Brindisi were also conquered by the Saracens (Arab troops from North Africa) in the 9th century.

Fear of frequent raids and the increasing submergence of the port facilities under rising sea levels gradually caused the inhabitants to flee to the villages in the hinterland. The long history of malaria in the lowlands may also have contributed to the retreat to higher ground.

The few remaining inhabitants lived in the former temples on the acropolis. Even the Messapic chamber tombs were sometimes used as living quarters. Egnazia fell into ruin, Monopoli grew and the town of Fasano was born. This once important ancient city was abandoned between the 13th and 14th centuries.

In 1745 the ancient remains were rediscovered and schematically mapped for the first time, but in the 19th century they were repeatedly and systematically plundered. It was not until 1912 that a scientific archaeological excavation began, which continues to this day. https://www.comune.fasano.br.it/pagina55_egnazia-il-parco-archeologico.html

The emergence of cave villages in Apulia in the Middle Ages

Perhaps as a result of the constant threats on the coast, or perhaps as a result of the iconoclastic controversy in the Byzantine Empire, a fascinating cave village developed in the area around Fasano from the 10th century onwards. The Byzantine iconoclastic controversy was a dispute between the Orthodox Church and the Byzantine imperial family over whether divine beings could be depicted in images. At times, celibacy was forbidden and monks were forced to marry. It is said that 30,000 Byzantine monks fled to Italy, and apparently monks of Greek Orthodox background also sought refuge in the many caves of Lama d’Antico or found a suitable retreat as hermits.

With the Islamisation of Sicily in the 9th century, monks also fled from there to Calabria and Puglia. The Rashidun Caliphate, the first Muslim state, was established in 632 and quickly conquered much of Persia and former Roman territories in the Levant and North Africa. From there they launched raids into Europe; in Sicily they ruled for 260 years from 831. Sicily benefited from the Muslim occupation: it experienced a period of prosperity and became cosmopolitan and multi-confessional.

Cave churches or entire medieval cave settlements can be found all over Puglia, of which Lama d’Antico is one of the most important.

Photo: Orubino, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Photo2023, CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The cave village of Lama d’Antico near Fasano

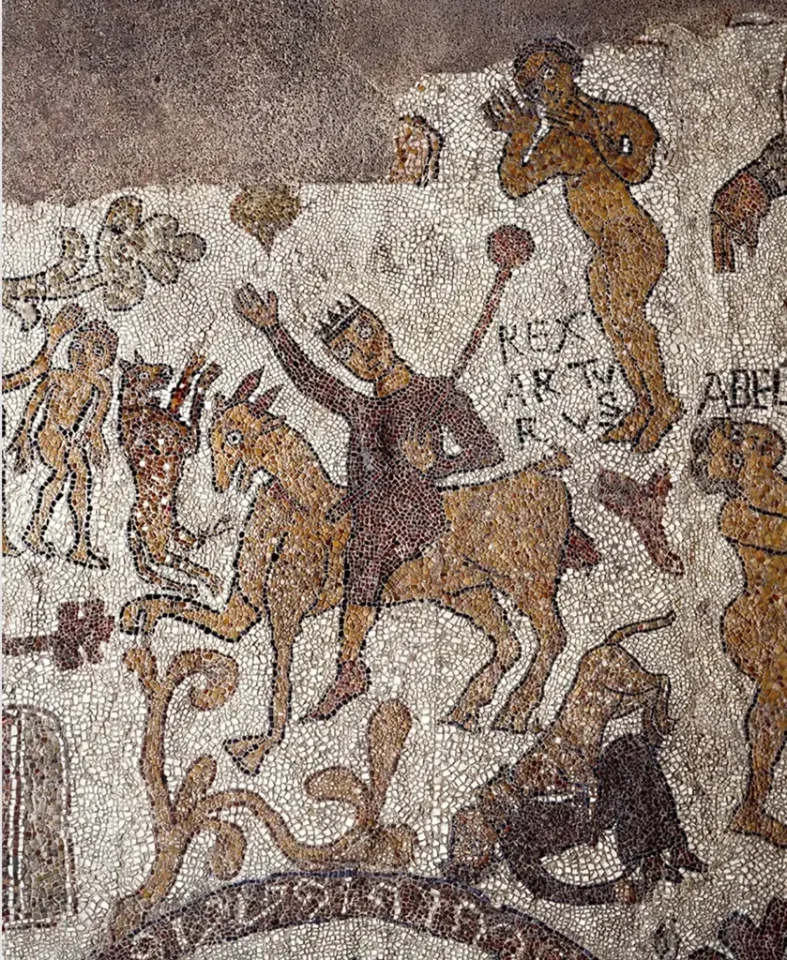

The rocky caves on the edge of a dry riverbed, inhabited since the Neolithic Age, were deliberately enlarged and permanently inhabited in the early Middle Ages. The frescoes (11th-13th centuries) in the caves, which were used as Christian places of worship, testify to the increasing fusion of the Greek-Byzantine pictorial tradition with Latin imagery and forms.

The 30 or so caves of Lama d’Antico still preserve visible traces of their former use: rainwater cisterns dug into the rock, pits for storing crops and food, wall niches and holders for oil lamps, couches and shelves carved into the tuff – until the 16th century, people here used nature in a very archaic way. It is thought that several hundred people lived in this cave village, but by the end of the Middle Ages they had moved to larger and more fertile centres.

https://www.brundarte.it/lama-dantico-fasano-br/

https://www.facebook.com/Lamadantico

Photo: Floliva, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Griko – a language as a surviving time capsule

In the 10th and 11th centuries, Byzantine rule brought with it a significant influx of Greek settlers from the eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans, Asia Minor, the Middle East and North Africa. In addition to the long-standing Greek influence on religious practices and representations, linguistic islands of the so-called Griko have actually survived to the present day. A language with elements of ancient Greek, Byzantine Greek and Italian, it is still partially spoken between Gallipoli, Òtranto and Lecce. As late as the 1970s, 20,000 people still spoke it in Calimera and the surrounding villages.

The Normans take over – Puglia blossoms again

At the beginning of the 11th century, the Lombards, Byzantines and Saracens were joined by new foreigners who would leave a lasting mark on Puglia: the Normans. Descendants of the Vikings who had conquered the northern French coast from Scandinavia, these landless knights from the French region of Normandy set out for Puglia. They quickly established themselves and by the middle of the 11th century their rule was extensive, ending the Byzantine era in southern Italy. By the 12th century, the Norman Empire (known as the Kingdom of Sicily from 1130), with its capital in Palermo, was the most modern, organised and culturally prosperous part of Europe, and the Arab-Muslim component in Sicily played a decisive role in its splendour.

During the Norman period, the productivity and growth of the cities increased sharply, while the large estates in the hinterland concentrated on cereal cultivation – it was not without reason that so many Normans came here to take possession of fertile land. In the coastal areas, land ownership was more fragmented due to the higher population density, and profitable cereal farming was not viable.

As a result, olive cultivation was revived in the coastal lowlands and along the riverbeds. The red, fertile soil that had accumulated here and the milder climate provided ideal conditions. By the end of the 13th century, olive cultivation was well established, often in combination with almond trees. It is interesting to note that the cultivation is quite extensive: existing wild olive plants are isolated and pruned, rather than new cuttings being planted in a regular pattern. This has led to the rather wild-looking olive groves that can still be found in the area today.

Photo: Ysogo, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Crusades, pilgrims to the Holy Land and their legacy

As has always been the case, Puglia has been strongly influenced by external forces. With the beginning of the Crusades, contacts with the Byzantine and Muslim worlds became particularly intense. The first crusade took place in 1095, when Pope Urban II called for the reconquest of Palestine, which had been conquered by the Arabs in 637. His call was followed by a huge army of armed laymen who were promised the remission of all their sins. Armies of knights then set out from France, Germany and Italy. Other Crusades to the Orient followed, which lasted until the end of the 14th century.

The Apulian Adriatic ports of Barletta, Bari, Brindisi, Otranto and Taranto served as convenient embarkation and disembarkation points for the crusading troops. The towns profited greatly from this traffic; Bari even managed to establish one of the most popular Christian pilgrimage sites of the Middle Ages by procuring, or rather robbing, the remains of Saint Nicholas of Myra. It is from this saint that our tradition of giving children something sweet in their boots on 6 December originates.

Photo: Touring Club Italiano 1930, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Vers75, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

With the establishment of Christianity, believers made their way not only to Jerusalem but also to Rome to visit the tombs of the apostles Peter and Paul. From the 9th century, the routes from England and the Frankish Empire to Rome were known as the Via Francigena, a name that gradually came to be used for the continuation of the old Roman roads Via Appia and Via Trajan. These routes took pilgrims to the ports of Puglia, Siponto, Bari, Egnazia, Brindisi, Otranto, ‘finis italiae’ (Santa Maria di Leuca) to embark for the Holy Land. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, the Via Francigena was at its most important, both as a pilgrimage route and as the main trade and military route between north and south. https://visit.puglia.it/en/via-francigena-stages-in-puglia-of-the-walk-from-canterbury

Although their intentions were seldom friendly, the Saracens, Ottomans, Greeks, French and many others have left their mark on Puglia’s culture. The architectural influences are most visible: the further south you go, the more the white plastered buildings, with their flat roofs, vaults and arcades, recall the Orient. Norman battlements and defiant towers have remained as stylistic elements well into modern times. The frescoes and mosaics in churches and monasteries retained their Greek-Byzantine imagery long after the fall of Byzantium and have survived to the present day.

The excellent wines of Puglia would be inconceivable without exchanges with Greece and the Levant; the abundance of traditional antipasti and sweet delicacies cannot deny their affinity with Arabic, but also Spanish and French cuisine. The combination of the traditional pizzica dance with oriental or African trance rituals is also interesting, but that would require a separate article…

Photo: Acquario51, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Teo1965, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The Swabian King Frederick II and his legacy in Apulia

In 1215 the Swabian king Frederick II, a grandson of Emperor Barbarossa, inherited the crown of the Kingdom of Sicily. Frederick II left an indelible mark on Puglia: in addition to numerous grand buildings, he reformed the laws and administration of the empire in a way that was modern for his time. He promoted science and culture, surrounded himself with Muslim scholars and writers, and settled the Apulian town of Lucera with Saracens, a provocation unacceptable to his contemporaries. The mystical aura of his castle, Castel del Monte, near Andria, is still intact and well worth a visit.

https://museipuglia.cultura.gov.it/musei-puglia/castel-del-monte/

Photo: Holger Uwe Schmitt, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Pakycassano, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The decline of the Apulian ports and the crisis of the 14th century

With the end of the Swabian period around 1268, the relative independence of Puglia came to an end, especially with the end of the Crusades and the rise of Venice as the dominant naval power in the Adriatic and the eastern Mediterranean. With the help of the Pope, the French royal family of Anjou took control of the southern Italian kingdom. After long struggles, the Kingdom of Naples, as it was now called, including Puglia, came under Spanish-Habsburg rule for 200 years from 1504.

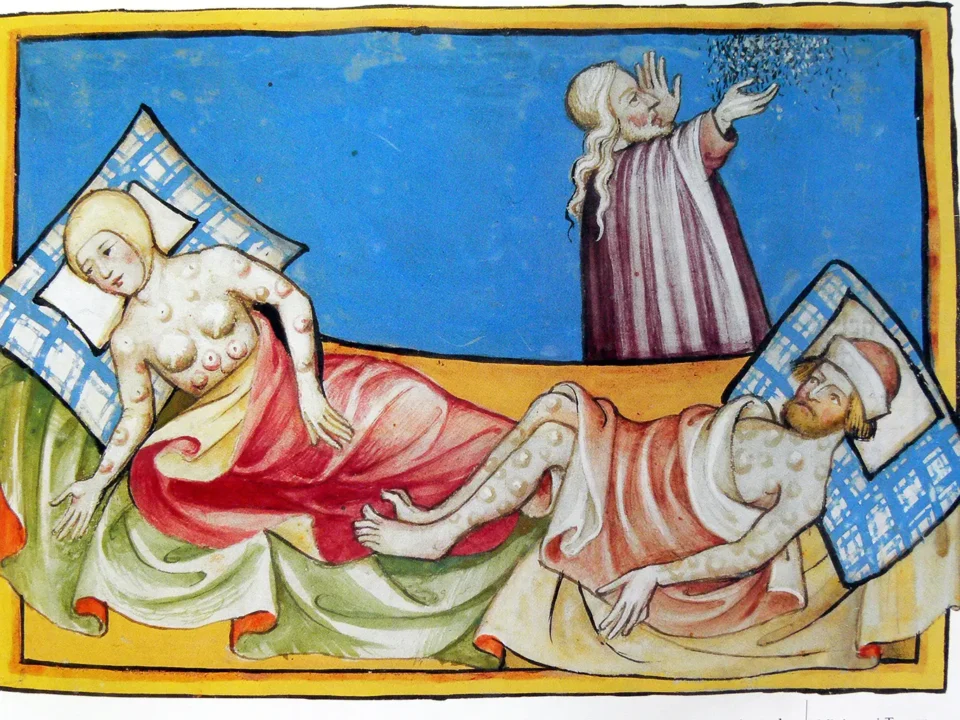

From the middle of the 14th century, a plague epidemic of unprecedented proportions ravaged the whole of Europe, killing around half the population on Italian soil. Combined with famines caused by crop failures and a previously rapidly growing population, the plague led to a prolonged demographic and productive crisis in Puglia. The countryside was partially depopulated, the numerous loose micro-settlements dissolved, and there were no longer enough people to work the fields as serfs. Maritime trade was also severely restricted for fear of new epidemics, and the economy virtually collapsed. Only the larger settlements survived.

Photo: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Interesting link to this topic: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1543/effects-of-the-black-death-on-europe/

The next article will look at how the design of the land and buildings that characterise our region of Puglia so uniquely came about.

How did the masseria develop in Puglia after the Middle Ages?

Fancy a Mediterranean crossover?

Although every Pugliese is rightly proud of his or her typical traditional cuisine, the regional cuisine cannot deny its influences from all parts of the Mediterranean. Nor can its buildings, its art, its music…

Would you like to experience this rich and unique mixture for yourself? You can start at our Masseria – book your stay here